As humans, our quest for a longer, healthier life has been central to the progress of science and medicine. Over the last century, life expectancy has dramatically increased, especially in high-income countries. However, this rise has started to slow down in recent decades, leading many researchers to question whether radical life extension—where humans could routinely live beyond 100 years—is a realistic goal for the 21st century.

A recent paper published in Nature Aging explores this very question, providing a detailed analysis of life expectancy trends across some of the world's longest-lived populations.

Life Expectancy Trends: Where Are We Now?

The study highlights that during the 20th century, life expectancy at birth increased by approximately 30 years in high-income countries. This significant rise was primarily due to improvements in public health, medical advancements, and reductions in infant mortality. By 1990, however, the pace of these improvements began to slow.

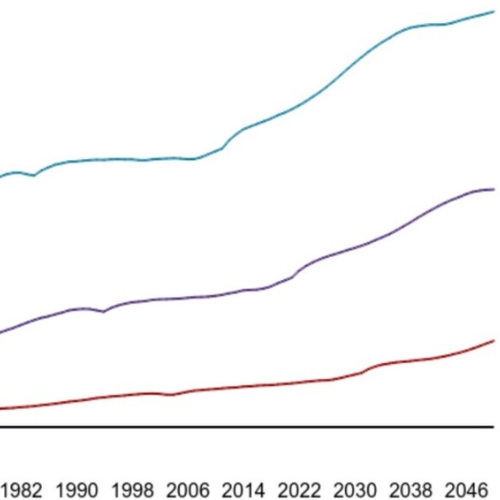

Researchers analysed data from 1990 to 2019 across eight countries with the longest-lived populations—Australia, France, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland—along with Hong Kong and the United States. The findings were stark: improvements in life expectancy have been decelerating.

For instance, while Hong Kong and South Korea saw rapid gains between 1990 and 2000, the most recent decades have shown much slower progress. In most populations, the rate of increase in life expectancy fell below 0.2 years per year, which is far less than the 0.3-year annual improvement required to meet the definition of radical life extension.

What is Radical Life Extension?

Radical life extension is defined in the paper as an increase in life expectancy by three years per decade, or 0.3 years annually. In this context, life expectancy at birth would need to reach around 110 years for such a scenario to occur.

However, the authors argue that such an extension is implausible this century unless significant breakthroughs in slowing biological ageing are achieved.

"The authors' definition of 'radical life extension' is only a 22-year increase in life expectancy—not that radical! But they go on to say 'unless the processes of biological ageing can be markedly slowed, radical human life extension is implausible in this century,' and they have not considered 'yet-to-be-developed medical advances,'" commented Adrian Cull, founder of the Live Forever Club, and an advocate for longevity.

Mortality Compression and Lifespan Inequality

Two critical concepts discussed in the paper are mortality compression and lifespan inequality.

Mortality compression refers to the shrinking window between the ages at which most people die. Lifespan inequality is the variation in ages at death within a population. The study found that since 1990, lifespan inequality has declined across all long-lived populations. This means that most people are dying within a narrower range of ages, typically between 70 and 90, as opposed to some living much longer than others.

While this might seem like a positive trend, it also suggests a limit to how much further we can extend life expectancy using existing medical interventions.

As Cull noted, merely tackling individual diseases will not push us past the so-called "natural" limit of 120 years. Instead, new therapies targeting the root causes of ageing are necessary for radical life extension to become a reality.

Why Radical Life Extension is Implausible in This Century

The authors point out several reasons why radical life extension is unlikely to occur in the 21st century.

One major factor is the deceleration in life expectancy improvements. Another reason is that to increase life expectancy at birth by even one year, there needs to be a significant reduction in mortality rates across all ages.

For example, to raise life expectancy for Japanese females from 88 to 89 years, death rates from all causes at all ages would need to drop by over 20%. For males, a similar increase would require a 9.5% reduction in total mortality.

These numbers illustrate the immense difficulty in extending human lifespan through traditional medical means. Even if all major causes of death were reduced by significant margins, the gains in life expectancy would be relatively modest.

Tackling Biological Ageing

However, not all hope is lost. The paper notes that radical life extension could become feasible if we can dramatically slow down the processes of biological ageing.

This is where the field of geroscience comes into play. Geroscientists study the biological mechanisms of ageing and are working on therapies that aim to delay or even reverse the ageing process. These include potential treatments like senolytics, which clear out damaged cells, and interventions targeting the hallmarks of ageing, such as DNA damage, inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction.

As Cull optimistically put it: "Rejuvenation treatments have barely reached the clinic yet, so predictions will radically change with 2nd and 3rd generation therapies targeting the hallmarks of ageing."

Indeed, if therapies that target biological ageing become widely available and prove effective, they could lead to significant extensions of human lifespan. This would represent a "second longevity revolution," as the authors describe, similar to the one experienced in the 20th century due to advancements in public health.

What Would Radical Life Extension Look Like?

If radical life extension were to occur, what might the demographic landscape look like? According to the paper, for life expectancy at birth to reach 110 years, more than 70% of females would need to survive to age 100. Additionally, 24% of females would need to live beyond 122 years—the current record for the longest human lifespan, held by Jeanne Calment, who died at 122 years old in 1997.

These numbers highlight just how far we are from achieving radical life extension. To reach these milestones, death rates at all ages would need to be reduced by up to 88%. This would likely require medical breakthroughs that eliminate most major causes of death, as well as therapies that extend the human body's functional lifespan well beyond its current limits.

Role of Medical Advances

The paper emphasises that while current trends make radical life extension unlikely, future medical advances could change the narrative. Researchers have yet to fully explore the potential of gerotherapeutics—drugs and treatments designed to target the biological processes of ageing. If these therapies can significantly slow down ageing, they could open the door to dramatic increases in life expectancy.

One key takeaway from the paper is that life expectancy predictions should not be based solely on linear trends from the past. Instead, they should account for potential breakthroughs in medicine that could drastically alter our understanding of ageing and lifespan.

The Economic and Societal Implications of Radical Life Extension

If radical life extension were to become a reality, the economic and societal impacts would be profound. Longer lifespans would require significant changes to retirement systems, healthcare, and social services. In countries where pensions are tied to age, for example, a large increase in the number of centenarians could strain public finances.

There would also be ethical and philosophical questions to consider. If only certain populations or individuals had access to life-extending therapies, it could lead to further inequalities in health and wealth. Policymakers would need to carefully navigate these challenges to ensure that life extension benefits society as a whole, rather than deepening existing divides.

Glass Mortality Ceiling: Are We Nearing a Limit?

The paper introduces the concept of a "glass mortality ceiling," which represents a soft limit on how much further we can extend life expectancy using current medical interventions. This ceiling is not an absolute limit, but it indicates that further gains in life expectancy are becoming progressively harder to achieve.

While medical advancements have extended human life, the fundamental biological processes of ageing still pose a significant barrier to radical life extension. As the paper argues, breaking through this glass ceiling would require innovations that target the underlying causes of ageing itself, rather than simply treating individual diseases.

What Can We Expect for the Rest of the Century?

So, what does the future hold for human life expectancy? The authors suggest that radical life extension is unlikely to occur in high-income countries within the next century. However, they do leave the door open for breakthroughs in ageing science that could change this prediction.

"Just tacking individual diseases is not going to push us past the 'natural' 120-year limit. But rejuvenation treatments have barely reached the clinic yet so predictions will radically change with 2nd and 3rd generation therapies targeting the hallmarks of ageing," Cull notes.

The study also points out that while radical life extension may not occur in high-income countries, it could happen in low- and middle-income nations that have not yet experienced the full benefits of the first longevity revolution. In these countries, improvements in public health and medical care could still lead to dramatic increases in life expectancy.

Balanced Outlook on Life Extension

In conclusion, the paper provides a balanced outlook on the future of life extension. While the idea of radical life extension remains implausible for now, the potential for future breakthroughs in ageing science could change that narrative. For now, the focus should be on continuing to improve public health, advancing geroscience, and preparing society for the possibility of longer lifespans.

As we look toward the future, it’s clear that the road to radical life extension is fraught with challenges. But with continued advancements in science and medicine, there’s hope that we might one day push beyond the limits of human longevity.

For now, we celebrate the extraordinary gains in life expectancy that humanity has already achieved, while remaining optimistic about what the future may hold for extending life even further.

The study was led by S. Jay Olshansky from the University of Illinois at Chicago.