Key points from article :

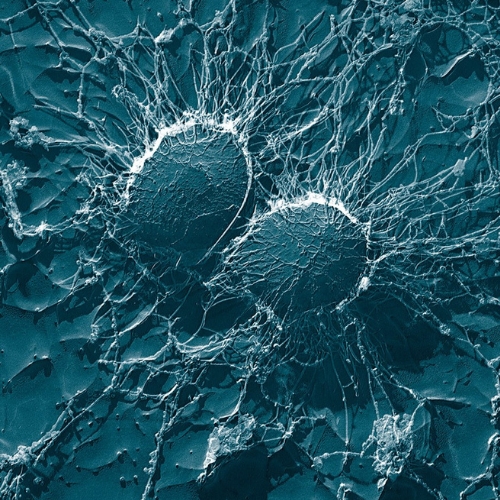

A major study involving more than 34,000 people has taken an important step toward defining what a truly “healthy” gut microbiome looks like. Led by microbiome researcher Nicola Segata at the University of Trento and collaborators in the large PREDICT programme run by Zoe, the research analysed which bacterial species most consistently correlate with low inflammation, healthy cholesterol levels, good blood sugar control and favourable fat distribution. The work helps clarify why previous microbiome tests have been difficult to interpret: while diversity matters, identifying which specific microbes support or undermine health has been much harder.

The team focused on 661 bacterial species present in at least 20% of participants, ultimately identifying the 50 species most strongly linked to good health and the 50 most associated with poorer outcomes. Surprisingly, 22 of the “good” species were previously unknown to science. People without medical conditions had more of these beneficial microbes than less healthy individuals, reinforcing the microbiome’s wide-ranging role in immunity, metabolism and even ageing. Many of the key species came from the Clostridia class, especially the Lachnospiraceae family, which included both helpful and harmful members.

Diet played a clear role in shaping these microbial patterns. Participants eating plant-rich, fibre-heavy diets with fermented foods tended to host more of the health-associated microbes, while diets high in ultra-processed foods aligned with species linked to poorer outcomes. Still, 65 microbes didn’t fit neatly into either “good” or “bad” categories, underscoring the complexity of microbial ecosystems and how their effects depend on interactions with other bacteria, individual strains and overall diet.

The findings allowed researchers to develop a 0–1000 “gut health score,” now used in Zoe’s commercial gut tests. Experts stress that this framework is a starting point rather than a definitive answer, as microbiomes shift with age, environment and medication use. Larger global studies will be needed, but this work offers one of the clearest maps yet of how our gut bacteria relate to health—and could eventually guide personalised diet recommendations to optimise an individual’s microbiome.