Key points from article :

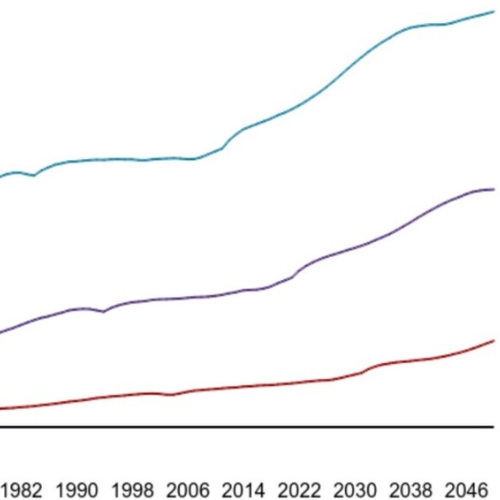

A new study led by Johanna Stärk at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology sheds light on one of biology’s long-standing mysteries — why females, on average, live longer than males. Published in Current Biology, the research offers the most comprehensive comparison yet of lifespan differences across 1,176 species of mammals and birds. The findings reveal a striking pattern: in about 72% of mammal species, females outlive males by roughly 12–13%, whereas in 68% of bird species, the trend reverses, with males living about 5% longer than females.

The team’s analysis supports the idea that sex chromosomes play a key role in longevity. In mammals, females have two X chromosomes, which may provide a genetic “backup” against harmful mutations, while males, with an X and Y, lack this protection. In birds, the situation flips — females have two different sex chromosomes (Z and W), while males have two Zs, suggesting that the sex with mismatched chromosomes (the heterogametic sex) tends to live shorter lives.

However, the study found that evolutionary and behavioural factors also influence longevity. In species with polygamous mating systems — such as gorillas or chimpanzees — males face intense competition for mates, often evolving larger body size or showy traits that drain energy and increase risk. These costly adaptations, along with frequent fighting, may shorten male lifespans. In birds, similar dynamics apply, but the effects are less pronounced because females bear the genetic cost of heterogamy.

Interestingly, the researchers also discovered that the sex investing more in offspring care generally lives longer — often the female in mammals. This may offer an evolutionary advantage, ensuring survival until young reach maturity. Even so, exceptions exist: for instance, female birds of prey live longer despite higher territorial aggression and size. The study concludes that while environmental and behavioural factors can narrow the gap, biological and genetic differences mean men and women — like their animal counterparts — will likely continue to age differently.