Key points from article :

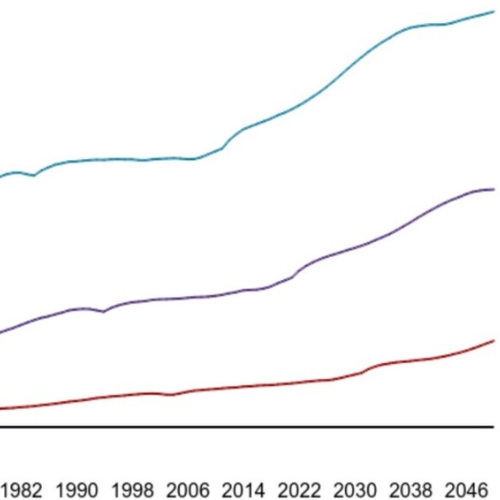

A new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by Johannes Hagen, Lisa Laun, Charlotte Lucke, and Mårten Palme investigates how income levels have influenced life expectancy in Sweden over the past 60 years. Using comprehensive population and mortality data, the researchers reveal a striking finding: the gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest Swedes has grown substantially, even as overall income inequality declined for much of the 20th century.

From the 1960s to the 2010s, the life expectancy gap between the top and bottom income brackets increased from 3.5 to 10.9 years for men, and from 3.8 to 8.6 years for women. Surprisingly, this widening health divide occurred despite a reduction in income inequality and increased public spending on health and welfare during much of the same period. This challenges the “absolute income hypothesis,” which holds that rising incomes alone lead to better health outcomes.

The researchers also examined which causes of death contributed to this growing gap. Circulatory diseases were the biggest driver of longer lives, especially in higher-income groups. Cancer mortality, meanwhile, showed a particularly steep income gradient among women. The most significant disparities, however, were tied to preventable deaths, such as those related to smoking, alcohol use, and lifestyle—suggesting that healthier behaviours have spread more rapidly among wealthier individuals.

The findings underscore that simply redistributing income may not be enough to close health gaps. Targeted public health efforts, especially those that encourage healthier behaviors among lower-income populations, are essential. The study also highlights growing equity concerns for social systems like pensions, which may inadvertently benefit higher earners more as longevity increases.