Ageing is a natural process that comes with various changes in our body, some of which are more visible, like wrinkles or gray hair, and others are less obvious but impact health. One of these hidden changes happens in our gut microbiome, the diverse community of microbes that live in our digestive system. Recent research has delved into how an aged gut microbiome can accelerate ageing symptoms, even in young individuals.

Specifically, a study involving mice has shown that transferring the gut microbiome from older mice to young mice induces signs of vascular and metabolic ageing. These findings shed light on the gut's role in ageing and open up intriguing possibilities for delaying age-related diseases.

Understanding the Gut Microbiome and Ageing

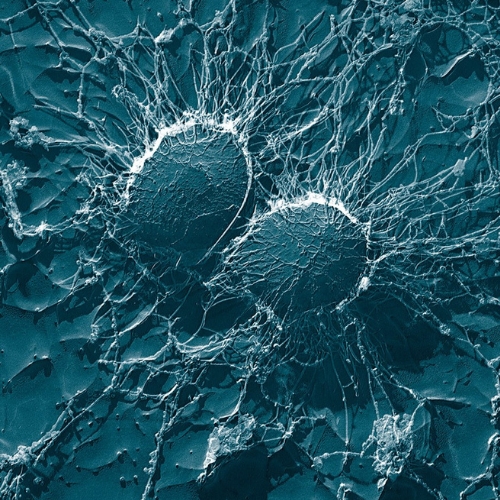

Our gut microbiome is a bustling ecosystem made up of trillions of bacteria, viruses, and fungi. These microorganisms are more than passive inhabitants; they play a significant role in our digestion, immunity, metabolism, and even mood. As we age, however, the gut microbiome undergoes changes—a phenomenon known as "dysbiosis."

In older adults, gut microbial diversity often decreases. Beneficial bacteria that support digestion and immunity may decline, while harmful bacteria might increase. This imbalance disrupts the gut’s normal function, contributing to chronic inflammation and impaired immune response. These age-related changes in the gut microbiome are linked with several age-associated conditions, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and neurodegenerative diseases.

The study we’re exploring takes this connection a step further, examining whether an aged gut microbiome can induce ageing symptoms in younger hosts. By studying mice, researchers aimed to find out if the microbial community alone could accelerate ageing, offering new insights into the gut's role in age-related health decline.

Fecal Microbiome Transfer (FMT) – A Unique Experiment

One of the most fascinating aspects of this study is the use of Fecal Microbiome Transfer (FMT), a technique that allows researchers to transplant gut bacteria from one individual to another. In this study, researchers transferred fecal microbiota from older mice into young, healthy mice to observe any changes in their health. The goal was to determine whether an aged microbiome would induce symptoms of ageing in the younger mice.

FMT is not new; it’s used in clinical settings to treat infections and other gut-related conditions. However, using it to study ageing is a unique approach. By giving young mice the microbiome of older mice, the researchers created a model that would help them understand if an aged microbial community alone could prompt ageing in a younger host.

How the Aged Microbiome Affected Young Mice

The results of this FMT experiment were striking. The young mice that received the aged microbiome exhibited several changes typically associated with ageing, including metabolic issues, vascular dysfunction, and even telomere shortening in certain tissues. Let’s break down some of the most important findings.

1. Body Weight and Metabolism

After the aged-to-young FMT, young mice started to lose weight, despite maintaining the same amount of food intake as before. Researchers noted that the young mice's metabolism seemed impaired, a common feature of ageing. This shift wasn’t just about body weight but also affected various organs, including the liver, spleen, and adipose tissues, where significant weight loss was observed.

2. Blood Glucose and Insulin Resistance

The young mice with the aged microbiome also showed signs of glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. Essentially, their bodies were less efficient at processing sugar, leading to higher blood glucose levels. These metabolic disruptions are often seen in conditions like diabetes and are linked to ageing. This result suggests that the aged microbiome directly affects glucose metabolism, possibly increasing the risk of age-related metabolic diseases.

Gut-Vascular Connection

One of the most groundbreaking discoveries in this study is how the aged microbiome impacted the blood vessels of young mice. This connection between gut health and vascular health, often referred to as the "gut-vascular connection," is increasingly recognised as a crucial factor in overall health.

Endothelial Dysfunction and Inflammation

In young mice with an aged microbiome, the function of blood vessels declined. Endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, showed signs of dysfunction. This impairment affects the ability of blood vessels to dilate, a hallmark of ageing in the vascular system. The researchers noted increased inflammation and oxidative stress within the blood vessels of these young mice, further contributing to their premature vascular ageing.

Telomere Shortening in Vascular Tissues

The aged microbiome also led to telomere shortening in the vascular tissues of young mice. Telomeres are protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, and their length is often associated with cellular ageing. Shorter telomeres indicate that the cells are older biologically. The telomere shortening in blood vessels pointed to accelerated vascular ageing, suggesting that gut health might play a role in cellular ageing across the body.

Intestinal Impact – From Inflammation to ‘Leaky Gut’

The study didn’t just stop at observing the vascular effects; it also delved into how the aged microbiome impacted the gut lining itself. The intestinal lining acts as a barrier, keeping harmful substances out of the bloodstream. However, in the young mice with an aged microbiome, this barrier showed signs of weakness.

Increased Intestinal Inflammation

One of the initial responses in the young mice was intestinal inflammation. This inflammation is a reaction to the imbalance of gut bacteria, where harmful bacteria may outnumber beneficial ones. Chronic inflammation in the gut has far-reaching consequences, affecting not only digestive health but also the immune system and other organs.

The ‘Leaky Gut’ Phenomenon

As the gut lining became more permeable, or “leaky,” endotoxins—a type of bacterial toxin—entered the bloodstream more easily. This phenomenon, known as “leaky gut,” is linked to systemic inflammation and has been associated with various diseases, including cardiovascular diseases and autoimmune disorders. The study’s findings show that an aged microbiome can compromise gut barrier integrity, leading to harmful substances circulating throughout the body.

Shifts in the Microbial Community – Which Microbes Matter?

By analysing the gut microbial profiles of the mice after FMT, researchers observed distinct changes in the young mice’s microbiome. Specifically, certain beneficial bacteria that help regulate inflammation were missing or reduced in the young mice with an aged microbiome.

Loss of Beneficial Bacteria

Species like Bifidobacterium pseudolongum, known for their anti-inflammatory properties, were less abundant in the young mice with an aged microbiome. Bifidobacterium species help maintain a balanced immune response and reduce gut inflammation, so their decline is likely a factor in the increased inflammation observed in the young mice.

Increase in Harmful Species

On the other hand, harmful bacteria that produce pro-inflammatory compounds were more prevalent. The aged microbiome had a specific composition that promoted inflammation and weakened the gut barrier. This shift in the microbial community highlights how critical microbial balance is to gut health and, by extension, overall health.

Reversing the Damage – The Role of Metformin and Exercise

Given the profound impact of the aged microbiome on the young mice, researchers looked for ways to counteract these effects. They turned to metformin and exercise, both known for their potential anti-ageing benefits.

Metformin and AMPK Activation

Metformin, a drug commonly used to treat diabetes, has also shown promise in longevity studies. In this study, metformin helped reactivate a key enzyme called AMPK, which plays a role in cellular energy balance. By activating AMPK, metformin helped reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in the intestines, restoring some of the gut barrier's integrity.

Exercise as a Protective Measure

Exercise was another effective intervention. Through moderate exercise, AMPK levels in the intestines improved, leading to enhanced gut function and reduced inflammation. Regular exercise not only benefits muscle and heart health but also helps maintain gut health, as shown by its effects on the young mice with an aged microbiome.

Together, metformin and exercise offer a glimpse into possible interventions that could mitigate the harmful effects of an aged microbiome on the gut and vascular systems.

Can We Slow Down Ageing with Gut Health?

The findings of this study have far-reaching implications. They suggest that maintaining a balanced gut microbiome could help prevent or slow down some of the physical declines associated with ageing. With more research, scientists may be able to pinpoint specific bacteria or microbial compositions that could act as preventive treatments for age-related diseases.

As researchers better understand the gut-vascular connection, they may develop new therapies targeting the microbiome to prevent cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, and other ageing-related conditions. This study highlights the importance of lifestyle choices, like diet and exercise, in maintaining gut health and, by extension, vascular health.

Conclusion

This study offers a compelling look at how an aged gut microbiome can speed up ageing processes in young mice, affecting their metabolism, blood vessels, and even their gut barrier. The gut-vascular connection appears to be a critical piece in understanding how ageing affects our bodies, and maintaining a balanced gut microbiome might be key to healthier ageing.

Whether through diet, probiotics, exercise, or drugs like metformin, supporting gut health could become a cornerstone of anti-ageing strategies. So, next time you consider ways to stay healthy as you age, remember that your gut microbiome might hold some of the answers.

The study is published in the journal Antioxidants. It was led by Chak-Kwong Cheng from City University of Hong Kong.