Key points from article :

Oocytes avoid the wear and tear other kinds of tissues suffer by skipping a fundamental metabolic reaction.

Animal cells use an alternative metabolic pathway that avoids generating destructive free radicals.

This could open up new avenues for treating infertility as well as provide a blueprint for improving the longevity of other types of human cells.

“It’s extremely compelling data,” said Christopher Hine, an aging researcher.

Female reproductive organs — ovaries, fallopian tubes, a uterus — start aging once you enter your third decade of life.

“This paper sheds new light on this entire process,” said John Aitken, a reproductive biologist at the University of Newcastle Australia.

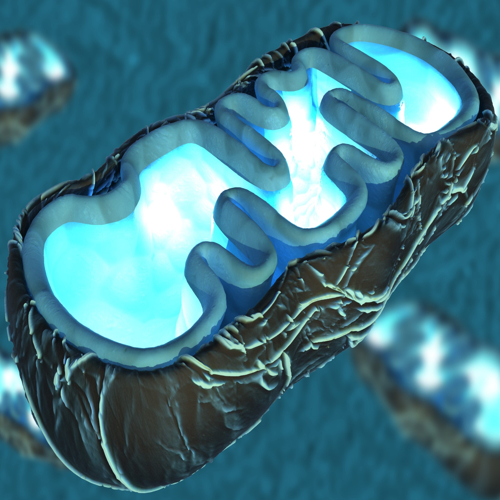

In human and frog oocytes, the mitochondrial genes that produce Complex I was turned off. “It’s considered to be the gatekeeper of this process,” Böke said.

By skipping Complex I, primordial oocytes are able to maintain a super-low energy state and remove a major source of electron leakage, and free radicals damage.

“The safeguards built here are more robust ... a testament to the importance of conserving reproduction,” said Johan Auwerx, a molecular biologist.

Testing for levels of Complex I subunits in oocytes of women with unexplained infertility to see whether an early exit from this quiescent state is the cause.

“If inhibition of Complex I is what drives these oocytes to stay in a quiescent state, then interventions that inhibit the activity of Complex I may help extend reproductive lifespan,” said Hine.

This research suggests studying data if women with diabetes who take metformin have improved ovarian reserves compared to others.

“If we can determine how these genes are selectively silenced in the oocyte, then there may be applications for this know-how in other cell types,” said Auwerx.

Research by the Centre for Genomic Regulation published in Nature