Researchers have long debated whether there is a limit to the human lifespan. A new study analyzing birth cohort data from 19 industrialized countries suggests that the maximum length of a human life may not be fixed. While historical patterns have shown mortality compression, meaning most people die within a similar age range, there have also been occasional episodes of mortality postponement, indicating that some people are living longer. The study found that cohorts born between 1910 and 1950 have experienced unprecedented mortality postponement but have not yet broken longevity records. As these cohorts reach advanced ages in the coming decades, longevity records may increase significantly. These findings suggest that if there is a maximum limit to the human lifespan, we have not yet approached it. However, achieving these potential increases in longevity depends on continued support for the health and welfare of the elderly and a stable political, environmental, and economic environment.

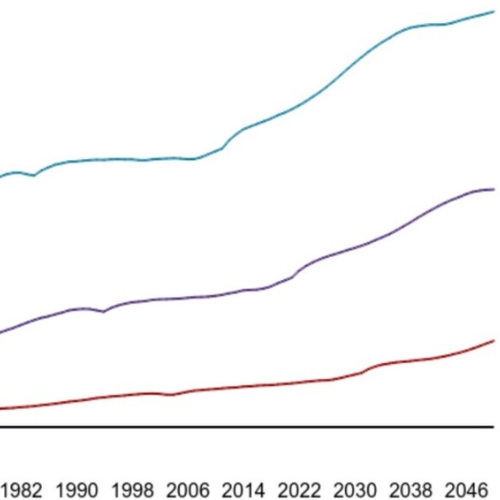

The study by University of Georgia reveals that the first episode of mortality postponement occurred for cohorts born in the latter half of the 19th century, with an increase of around 5 years in the Gompertzian Maximum Age (GMA), which is the age at which individuals reach an assumed mortality plateau. The increase was more pronounced for females than for males. This postponement may be related to improvements in public health and medical technology at the time.

A second, more significant episode of mortality postponement is affecting cohorts born between 1910 and 1950, who are currently aged between 70 and 110. The GMA for these cohorts may increase by as much as 10 years, depending on the country, with a potential increase in remaining life expectancy at age 50 by up to 8 years.

The slow increase in longevity records in recent years can be explained by the fact that older cohorts, who were too old to experience the current bout of postponement, have not yet broken longevity records. However, as younger cohorts who have experienced this postponement reach advanced old age, there is potential for longevity records to rise by the year 2060.

It is essential to note that these predictions depend on various factors, including the maximum mortality rate assumed by the study. Moreover, the potential to break existing longevity records depends on policy choices that support the health and welfare of the elderly, as well as political, environmental, and economic stability. The Covid-19 pandemic has demonstrated the vulnerability of elderly populations, highlighting the need for continued support in maintaining their health.

If the GMA increases as the current mortality experience of incomplete cohorts suggests, the implications for human societies, national economies, and individual lives will be substantial. This may lead to increased demands on healthcare systems, pension schemes, and social support services, requiring societies to adapt to these changes and prioritize the wellbeing of their aging populations.