Key points from article :

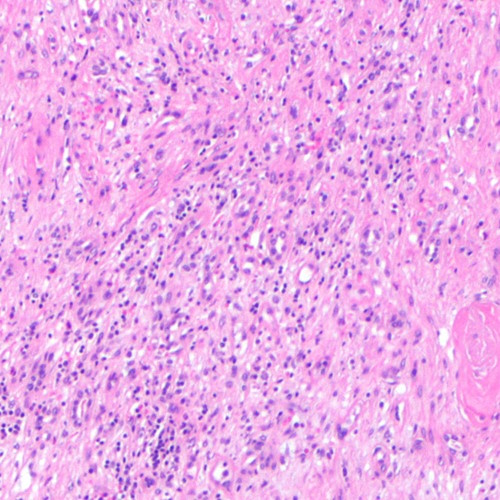

A new study from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health reveals how aging and chronic inflammation trigger a toxic buildup of iron in muscle stem cells (MuSCs), ultimately causing them to "rust to death" through a process called ferroptosis. Published in Nature Aging, the research uncovers how inflammatory signals disrupt the normal reading of DNA instructions in stem cells, particularly by silencing a gene called Kmt5a that helps regulate iron metabolism and stem cell rest cycles.

Using mouse models, scientists found that aged muscle tissue shows increased inflammation and abnormal activity in a receptor called CCR2, which interprets inflammatory signals. This overstimulation leads to the loss of Kmt5a activity. Without Kmt5a, DNA becomes less accessible, silencing protective genes and forcing stem cells into a constant state of activity—exhausting them and leading to fatal iron overload. In genetically modified mice lacking Kmt5a, 80% of MuSCs showed iron accumulation—70 times higher than in normal cells—and nearly a third showed signs of cell death and DNA damage.

The team also tested an anti-inflammatory drug, Bindarit, which restored Kmt5a levels and reduced iron buildup in aged mice, suggesting a promising therapeutic route. This work helps explain why older adults may simultaneously experience anemia (systemic iron deficiency) and iron overload in specific tissues like muscle and brain. Since ferroptosis is also implicated in diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson’s, the findings may have broader implications beyond muscle aging.

Moving forward, the Blanc lab is investigating how iron metabolism interacts with aging and epigenetics, and whether exercise can help mitigate these changes. Their goal is to better understand and eventually prevent the age-related loss of muscle stem cells—a key contributor to frailty, falls, and reduced quality of life in older adults.