Key points from article :

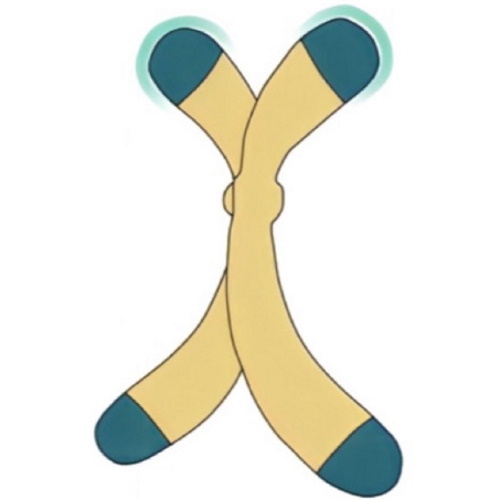

Researchers from Duke University and the University of California, San Francisco, have found that fat-tailed dwarf lemurs can temporarily reverse cellular ageing during hibernation. The study, published in Biology Letters, shows that these small primates extend the length of their telomeres—protective caps on chromosomes that typically shorten with age—while in a hibernation-like state.

To investigate this, the scientists observed 15 lemurs at the Duke Lemur Center before, during, and after hibernation. They created artificial winter conditions by gradually lowering temperatures and providing burrows for the animals to curl up in. Some lemurs were allowed to wake up and eat, while others remained in a deep, months-long torpor, living off stored body fat.

Genetic sequencing of cheek swabs revealed that lemurs in deeper hibernation saw their telomeres grow longer, while those that woke up and ate maintained stable telomere lengths. These findings were unexpected, as telomeres usually shorten over time. Researchers believe the telomere extension might help counteract cellular stress caused by the metabolic shifts of hibernation.

The effect was temporary—within two weeks of coming out of hibernation, the lemurs’ telomeres returned to their previous lengths. However, this process may contribute to their remarkable longevity. Unlike other primates of similar size, such as galagos, which live around 12 years, fat-tailed dwarf lemurs can survive for nearly 30 years.

A similar telomere-lengthening effect has been observed in humans exposed to extreme conditions, such as astronauts spending extended time in space or divers living underwater for months. The researchers hope studying these lemurs can help uncover ways to slow ageing in humans without increasing the risk of uncontrolled cell growth, which can lead to cancer.