As the global population ages, the health challenges associated with ageing become more pronounced. Among the most concerning of these is frailty, a state of heightened vulnerability and diminished physiological resilience. Frailty can lead to a cascade of adverse health outcomes, including an increased risk of falls, disabilities, and even mortality. In this context, understanding the role of frailty in ageing populations is crucial.

A recent study conducted in China explored the association between changes in the frailty index (FI) and the risk of all-cause mortality in older adults. The study aimed to investigate how a three-year change in FI influences the risk of death in older Chinese individuals, and how this relationship might differ across factors such as age, sex, and residence. This research contributes to the understanding of frailty dynamics and its implications for public health strategies in ageing societies.

What is Frailty?

Frailty is a clinical syndrome characterised by a decline in multiple physiological systems, leading to a reduced ability to cope with stressors. Frailty is typically assessed using the Frailty Index (FI), which quantifies an individual’s frailty based on accumulated deficits in health. These deficits include signs, symptoms, diseases, disabilities, and other health conditions. The FI is calculated as the ratio of the number of deficits a person experiences to the total number of possible deficits. A higher FI score indicates a greater degree of frailty.

The Research Study

The study, led by Liu et al., utilised data from the Chinese Longitudinal Healthy Longevity Survey (CLHLS), which follows a cohort of older adults across China. The team analysed the health data of nearly 5,000 participants, examining the relationship between changes in the FI over three years and the risk of all-cause mortality.

The primary focus of the study was to assess how a change in the frailty index over a three-year period impacts the risk of death. This study is particularly important because it goes beyond a snapshot of frailty at a single point in time and instead considers how frailty evolves, which can offer more insights into long-term health risks.

Study Design and Methods

The study followed 4,969 participants aged 65 and older, who were part of the CLHLS. These participants were tracked over a median follow-up period of approximately 4.08 years. The researchers used data collected from three separate surveys conducted in 2011-2012, 2014, and 2017-2018. A range of health metrics, including frailty indices, demographic factors, and lifestyle characteristics, were assessed.

The frailty index was calculated based on 38 health deficits, including chronic conditions, physical disabilities, cognitive impairments, and other health concerns. The participants were categorised as robust (FI ≤ 0.12), pre-frail (0.12 < FI ≤ 0.25), or frail (FI > 0.25), based on their FI scores at the beginning of the study.

The researchers divided the participants into groups based on their FI change over the three years between the surveys. These groups were:

- FI loss: Change in FI from baseline to follow-up was negative (indicating improvement in frailty).

- FI gain: Change in FI from baseline to follow-up was positive (indicating worsening frailty).

- Stable FI: Little or no change in FI.

The risk of all-cause mortality was assessed for each group, and Cox proportional-hazard regression models were employed to adjust for potential confounders, such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, physical activity, and other health indicators.

Key Findings

1. Increased Risk with FI Gain

The study found that a significant increase in FI (≥ 0.045) was associated with a 2.27-fold higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to those with a stable FI (change in FI between -0.015 and 0.015). This result suggests that individuals whose frailty worsened over the three-year period were at a much higher risk of dying.

2. Decreased Risk with FI Loss

On the other hand, those whose FI improved (i.e., decreased by more than 0.045) had a significantly lower risk of mortality. The hazard ratio (HR) for this group was 0.54, indicating a 46% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality compared to the stable FI group.

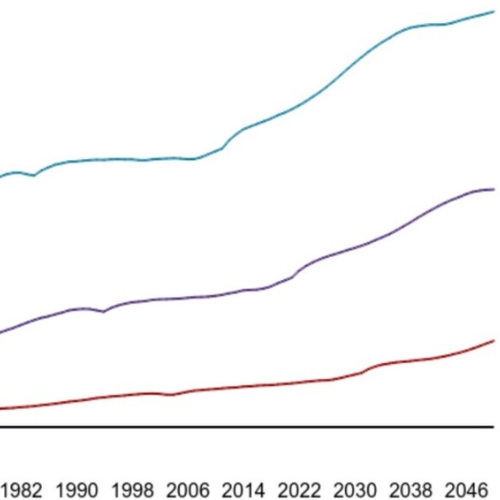

3. Nonlinear Dose-Response Relationship

The analysis revealed a nonlinear dose-response relationship between the change in FI and mortality risk. This means that the relationship between FI change and risk of death was not linear but instead followed a curve, where the risk increased rapidly as frailty worsened, especially for those with significant increases in FI.

4. Subgroup Analyses

The researchers further analysed how age, sex, and residence (urban or rural) influenced the relationship between FI change and mortality. The results indicated that age modified the association, with older individuals being more vulnerable to the negative effects of increased frailty. However, there were no significant differences observed by sex or residence.

5. Persistent Frailty and Mortality

The study also highlighted the risks associated with persistent frailty. For instance, individuals who remained frail over the study period had an increased risk of mortality compared to those who were pre-frail or robust.

Role of Frailty in Ageing Populations

The findings of this study underscore the importance of monitoring frailty in older adults. While frailty is often seen as an inevitable part of ageing, this research demonstrates that it is not a fixed state. Frailty can fluctuate, and these changes have significant implications for health outcomes, including mortality.

This dynamic nature of frailty suggests that interventions aimed at improving frailty, such as physical activity, better nutrition, and medical management of chronic conditions, could significantly reduce the risk of death in older adults. The study’s results align with previous research indicating that frailty is not only preventable but also reversible with appropriate interventions.

Implications for Public Health and Policy

The findings of this study have profound implications for public health policies, especially in countries like China, where the elderly population is rapidly increasing. By focusing on interventions that can help reduce frailty or slow its progression, it may be possible to improve the quality of life for older adults and reduce healthcare costs associated with frailty-related health conditions.

Targeted programs that focus on physical exercise, nutritional support, and regular health screenings for older adults could be beneficial in reducing the prevalence of frailty. Additionally, healthcare systems should incorporate frailty assessments into routine care for older adults to identify those at higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between frailty changes and mortality, there are several limitations to consider. The study was observational, meaning it can only establish associations, not causal relationships. Additionally, the frailty index was based on self-reported data, which may have introduced some biases.

Future research should aim to explore the long-term trajectories of frailty and its impact on various health outcomes beyond mortality. Multicenter studies with larger sample sizes, diverse populations, and detailed longitudinal data would provide a more comprehensive understanding of frailty’s role in ageing.

Conclusion

Frailty is a significant health concern for the ageing population, with profound implications for mortality and quality of life. The findings from this study show that the dynamic change in frailty, particularly an increase in the frailty index, is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality among older Chinese adults. Conversely, improvements in frailty can lower the risk of death, highlighting the importance of early intervention and continuous monitoring. By addressing the factors contributing to frailty and promoting interventions that enhance resilience, we can help improve the health outcomes of the elderly and mitigate the societal impacts of ageing.

The study is published in the journal BMC Geriatrics. It was led by researchers from Henan University of Chinese Medicine