Can Clearing “Zombie Cells” Help Us Age Better?

Aging is often described as a slow accumulation of wear and tear. But scientists are discovering that some of this damage may come from cells that refuse to die. These so-called “senescent” cells—sometimes nicknamed zombie cells—stop dividing but remain metabolically active, pumping out inflammatory chemicals that can harm surrounding tissue. A recent comprehensive review published in Drug Design, Development and Therapy explores how targeting these cells could transform the way we approach healthy aging.

What Are Senescent Cells—and Why Do They Matter?

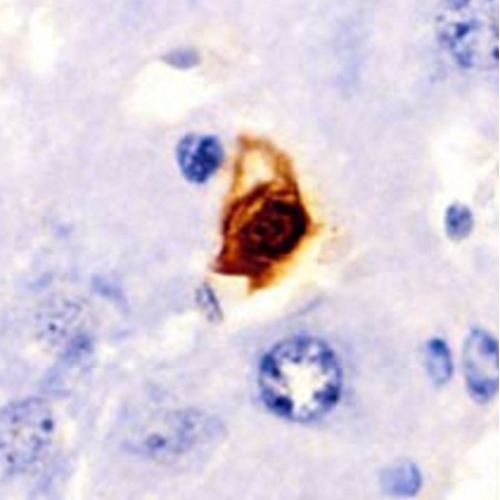

Cellular senescence is a natural process. When cells experience serious stress—such as DNA damage, telomere shortening, or oxidative stress—they permanently stop dividing. This acts as a protective mechanism, preventing damaged cells from turning cancerous and helping with wound healing early in life.

The problem arises later. As we age, senescent cells accumulate because the immune system becomes less efficient at clearing them. These lingering cells secrete a cocktail of inflammatory molecules known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). SASP includes cytokines like IL-6 and IL-8, growth factors, and enzymes that degrade tissue structure. Over time, this chronic inflammatory state contributes to many age-related diseases, from cardiovascular disease and diabetes to neurodegeneration and osteoarthritis.

Targeting Senescence: Two Strategies, One Goal

The review, led by Esther Ugo Alum and colleagues, examined over 260 studies published between 2014 and 2025 to assess emerging strategies aimed at controlling cellular senescence. Two main therapeutic approaches dominate the field: senolytics and senomorphics.

Senolytics are drugs designed to selectively kill senescent cells. These cells rely heavily on survival pathways that protect them from programmed cell death. By blocking those pathways, senolytics trigger apoptosis specifically in senescent cells while sparing healthy ones—at least in theory.

Senomorphics, by contrast, leave senescent cells alive but make them less harmful. These compounds suppress the SASP, reducing inflammation and tissue damage without eliminating the cells outright. This approach may be safer in contexts where senescent cells still serve useful functions, such as wound healing.

What Does the Evidence Show?

In animal studies, senolytics have produced striking results. Removing senescent cells in mice improves physical function, reduces inflammation, delays age-related diseases, and in some cases extends lifespan. For example, the combination of dasatinib and quercetin has been shown to improve cardiovascular function and reduce bone loss in aging mice.

Early human trials are more cautious but encouraging. In a small phase 1 study involving patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, intermittent dosing of dasatinib and quercetin reduced markers of senescent cells and improved physical performance. However, safety concerns remain. Some senolytics, such as navitoclax, can cause side effects like thrombocytopenia because they interfere with survival pathways also used by healthy cells.

Senomorphics may offer a gentler alternative. Drugs such as metformin and rapamycin—already approved for other indications—have been shown to suppress inflammatory signaling pathways like NF-κB and mTOR that drive the SASP. In both animal models and human studies, these compounds reduce inflammation and improve metabolic and immune function, even without directly killing senescent cells.

Beyond Drugs: Lifestyle as an Anti-Aging Tool

The review also highlights that lifestyle interventions can naturally modulate senescence. Regular exercise and calorie restriction consistently reduce senescent cell burden and dampen SASP-related inflammation in animal and human studies. These interventions improve mitochondrial function, reduce oxidative stress, and enhance immune clearance of senescent cells—effects that mirror, on a smaller scale, those seen with pharmaceutical approaches.

Challenges on the Road to Healthy Aging

Despite rapid progress, major hurdles remain. Aging is not classified as a disease, complicating regulatory approval for senescence-targeting drugs. Reliable biomarkers—such as p16^INK4a or β-galactosidase—are still imperfect for tracking senescent cells in patients. Long-term safety, optimal dosing schedules, and tissue-specific targeting also need further study.

A New Vision for Aging

Rather than treating individual age-related diseases one by one, targeting cellular senescence offers a unifying strategy: extend healthspan, not just lifespan. The authors conclude that combining senolytics, senomorphics, and lifestyle interventions may ultimately deliver the greatest benefit. Aging may be inevitable—but the biological processes that make it unhealthy could soon be optional.

The study is published in the journal Drug design, development and therapy. It was led by Regina Ejemot-Nwadiaro from Kampala International University, Uganda.