Fasting is everywhere — from celebrities endorsing intermittent fasting to clinics offering prolonged water-only fasts. Many believe it “resets” the body and reduces inflammation. But is that true?

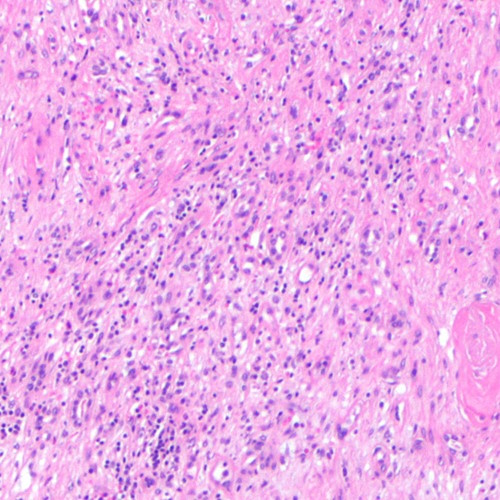

A 2025 systematic scoping review published in Ageing Research Reviews examined prolonged fasting (≥48 hours) and its effects on inflammation

. The findings challenge popular assumptions: rather than reducing inflammation, long-term fasting often increases inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP).

This blog explores the science in detail, including a fasting timeline that reveals what happens to your body hour by hour.

Inflammaging: Why Inflammation Matters

Chronic low-grade inflammation — often referred to as inflammaging — has emerged as one of the most important biological drivers of aging. Unlike acute inflammation, which helps the body fight infections or heal injuries, this persistent, simmering inflammation occurs silently and continuously, even in the absence of any obvious illness. Over time, it wears down tissues, disrupts normal cellular processes, and lays the groundwork for multiple chronic diseases.

Scientists have identified several biomarkers that reliably signal this hidden inflammation. Among the most notable are C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). Elevated levels of these molecules in the bloodstream are not just laboratory curiosities; they strongly predict a person’s risk of developing life-threatening conditions. High CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α levels are consistently linked with an increased likelihood of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, dementia, and various cancers. In other words, they act as warning signals for some of the most feared diseases of aging.

Because of this, effectively managing systemic inflammation has become a cornerstone of modern strategies to extend not only lifespan but also healthspan — the years of life spent free from serious disease.

The Review: How It Was Done

Researchers analyzed 4003 papers and included 14 human studies on fasting ≥48 hours. The studies measured CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α in participants who underwent water-only or modified fasting protocols.

Most studies found increased inflammation during fasting, though some showed normalization or reduction after refeeding.

Key Findings

CRP often doubled during fasting.

TNF-α and IL-6 showed mixed results: some increases, some no change, one decrease.

Refeeding (especially plant-based) often reduced CRP below baseline.

Why Fasting Raises Inflammation

Macrophage infiltration of fat tissue → cytokine release

Metabolic stress (ketones, cortisol, reduced insulin) → immune activation

Evolutionary mismatch: once adaptive, now potentially harmful in modern metabolic contexts

Daily Timeline: What Happens During Prolonged Fasting

Here’s a detailed breakdown of biological and inflammatory changes across a multi-day fast:

12 Hours

Blood glucose begins dropping as glycogen stores deplete.

Liver glycogenolysis maintains blood sugar.

Insulin falls, allowing fat breakdown to begin.

Inflammation: no major change yet.

24 Hours

Ketosis begins: liver produces ketones (β-hydroxybutyrate).

Autophagy (cellular cleanup) activates.

Cortisol rises to maintain energy balance.

Inflammation: CRP and cytokines remain stable in most studies.

36–48 Hours

Fat becomes primary fuel.

Growth hormone rises, protecting muscle.

Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) falls, reducing growth signaling.

Inflammation: CRP begins increasing in some participants. Early studies show mild inflammatory gene activation in fat tissue

72 Hours (3 Days)

Macrophage activity in fat tissue surges.

CRP spikes significantly in overweight individuals.

IL-6 and TNF-α rise in some studies, suggesting immune system activation.

Quiroz-Olguín et al. (2024) noted TNF-α decreased, showing variability.

4–7 Days

Deep ketosis achieved.

Adipose tissue inflammation peaks.

Transcriptomic signatures in fat show immune activation (Fazeli et al., 2020).

Symptoms: fatigue, irritability, sometimes flu-like aches.

Inflammation: CRP often doubles, TNF-α and IL-6 frequently elevated.

10–14 Days

Protein sparing deepens; fat continues as dominant fuel.

CRP may remain elevated, though some modified fasts show stabilization.

Grundler et al. (2021) reported CRP rising at day 7, then returning to baseline by day 14.

15–20 Days

In large observational studies (e.g., Wilhelmi de Toledo et al., 2019), CRP rose consistently regardless of fasting duration.

Risk of nutrient deficiencies rises without medical supervision.

Inflammation: often persistently high, unless carefully managed refeeding follows.

Refeeding Phase

Insulin rises, restoring glucose use.

CRP often drops below baseline (Scharf et al., 2022; Gabriel et al., 2022).

Not all markers normalize — IL-8 and ferritin sometimes remain elevated (Commissati et al., 2025).

Suggests the inflammatory surge may be transient and adaptive.

Practical Lessons

Short-term spikes in inflammation are normal.

When the body enters a prolonged fast, it doesn’t always respond with immediate healing or calm. Instead, research shows that levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and other inflammatory markers can temporarily rise. These increases don’t necessarily mean something is “wrong” — they may reflect the body’s adaptive response to the stress of fasting. Still, it’s important to recognize that the early stages of a multi-day fast are often accompanied by an inflammatory surge rather than a reduction.

Refeeding is not just important — it’s crucial.

How you break a fast matters as much as the fast itself. Studies demonstrate that plant-based refeeding — rich in whole foods, fiber, and antioxidants — helps inflammation return to baseline more quickly, sometimes even dropping below pre-fast levels. In contrast, refeeding with heavy, processed, or animal-fat–rich meals may prolong or worsen inflammatory stress. The refeeding phase essentially determines whether fasting leaves the body in a healthier state or not.

Individual responses can vary dramatically.

Not everyone experiences fasting the same way. Research indicates that lean individuals and those with healthy metabolisms may show different inflammatory patterns compared to overweight or obese individuals. For example, CRP spikes tend to be more pronounced in people carrying excess visceral fat. This variability means that prolonged fasting isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution and should be approached with personal context in mind.

Medical supervision is strongly advised.

While a short fast of 24 hours may be safe for many healthy adults, going beyond three to five days increases risks. These include electrolyte imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, and, as studies suggest, potentially harmful spikes in inflammation. Professional supervision can help ensure that the fast is conducted safely and that refeeding protocols are optimized for recovery.

Intermittent fasting may be a safer alternative.

For most people, intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating offers a more practical and lower-risk path. These methods allow for many of the same metabolic benefits — improved insulin sensitivity, better weight control, and enhanced cellular repair — without triggering the significant inflammatory surges often seen in prolonged fasts.

The Verdict

This comprehensive review overturns the popular belief that prolonged fasting universally reduces inflammation. In reality:

Fasting ≥48 hours often increases CRP and other inflammatory markers, at least in the short term.

Refeding seems to reverse these effects, but the long-term impact remains unclear. Until large, controlled studies confirm benefits, prolonged fasting should be approached with caution.

Prolonged fasting is not a magic bullet. It triggers complex metabolic and immune responses that can raise inflammation before lowering it. This may reflect an ancient survival mechanism — useful in food-scarce environments, but potentially risky in today’s context of metabolic disease.

If you’re curious about fasting, consider shorter protocols or intermittent fasting under medical guidance, and always prioritize safe, nutrient-rich refeeding.

The study is published in the journal Ageing Research Reviews. It was led by Isabella de Ciutiis from The University of Sydney.